The Templers (not to be confused with the earlier Mediaeval Knights TemplAr) were a religious group from the Lutheran Church in 17th century Germany. They believed that the Day of Judgment was near and that it was necessary to rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem so that all Jews would return to the Holy Land, which, they were convinced, would promote the second coming of Christ.

Because of such beliefs their Church expelled them in 1858 as heretics, but the Prussian Protestant Church supported their dream of living in the Holy Land. The first Templer community established a colony in 1875 in Haifa, a town then of merely 4,000 residents. Over the next 30 years other groups settled in Sarona (part of Tel Aviv), Wilhelma (Lod), Valhalla (Jaffa), Bethlehem of Galilee and Waldheim (Alonei Abba) At their peak they numbered 2,000.

In 1898, Kaiser Wilhelm II (Emperor of Germany) visited Jerusalem. His mother was Victoria, Princess Royal, the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria of Britain. I recall being told by Dr Cyril Sherer, my husband’s cousin, that she adamantly insisted a British doctor attend her daughter’s confinement. The delivery was complicated and, unfortunately, Wilhelm was born with a withered arm. He endured years of futile attempts to alleviate his condition – and over the years developed a hatred for Britain, maybe partially because of the doctor who had overseen his birth. He also began to hate his British mother, for he had developed an ‘unnatural’ affection for her (documented in his many letters to her) but she failed to respond to his needs.

And look what happened…. Wilhelm became the architect of World War 1 – an ill advised move. Germany lost to Britain – he was exiled to the Netherlands, where, appalled by Nazi atrocities in Europe, he said that for the first time in his life he was ashamed to be a German. But I digress –

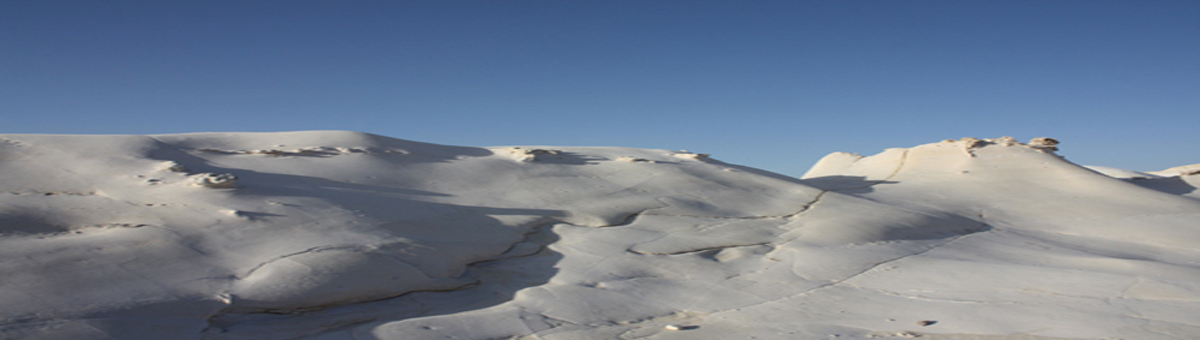

His triumphal entry to Jerusalem was greeted with cheering crowds including many Templers. Following the visit he allocated funds for them to purchase more land. They saw ‘Zion’ as their second homeland – they were not missionaries but wanted to establish a Kingdom of God together with the People of the Book. To come to such a desolate place as it then was, must have been like going to the moon. But they were industrious, initially focusing on farming. The climate was malarial and child mortality high but they persevered, draining swamps, planting fields, vineyards and orchards and employing modern farming techniques.

They operated steam-powered oil presses and flour mills, opened the country’s first pharmacies and hotels and manufactured essential commodities such as soap, cement and, of course, being German, beer.

The Miller’s house. Matthaus Frank

The first Templer house in Jerusalem was built by Matthaus Frank in rustic German style using local Jerusalem stone in place of timber. It was called The Miller’s House as it had a steam-powered mill and bakery on the property. It was on Emek Refaim, so named by the Templers, meaning Valley of the Ghosts, which led from Jerusalem, through the Valley of Elah (where David fought Goliath) and onwards to the coastal plain.

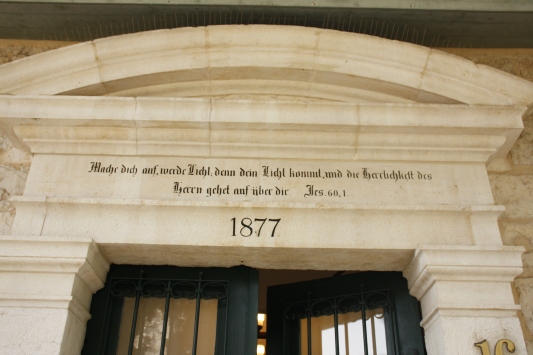

The settlers chose Jerusalem as their spiritual centre, because of its proximity to the Temple Mount. An ‘Old’ schoolhouse was built, then a ‘New ‘school and community building. The walls were 1m thick with arched windows. Several other distinctive Templer homes were built in this area. Abraham Fast built a home on Cremieux Street. He achieved fame as the proprietor of Fast’s Hotel, situated opposite the Jaffa Gate. He chose his timing well, for it coincided with the building of the railroad from Jaffa to Jerusalem by a French company so many engaged in its construction needed accommodation and food. Architect, Gottleib Bauerle built a splendid home on Lloyd George Street with many novel features. All of these buildings can still be seen, many with biblical texts carved in Gothic lettering above their doorways.

The Templers established a regular coach service between Haifa and other cities. This, plus, the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway undoubtedly boosted the burgeoning tourist industry. They opened small businesses, pastry shops, a travel agency, a photography shop and workshops not yet see in the city.

Over the years they remained fiercely patriotic to their German roots. During WW1 many enlisted the German army to fight on the battlefields of Europe where they died. A well tended cemetery exists on Emek Refaim – a memorial to 24 of their fallen. But Germany’s defeat was a disaster for the Templers, particularly when Palestine came under British control and they were treated as enemy aliens. In 1918 the British sent 850 of them to internment camps in Egypt and two years later deported 350 to Germany, confiscating their property. A small number returned after the war but things were never the same, although life for the Templers remained peaceful.

However, all this changed with the rise of Hitler in the early 1930’s, with Naziism becoming an attraction for the younger Templers. By 1933 a Nazi branch was established in Haifa and other communities followed suit, ensuring that Naziism permeated all aspects of their life. The British Boy Scouts and Girl Guides in the German Colony were replaced by the Hitler Youth and League of German Maidens. Workers joined the Nazi Labour Organisation and members greeted each other in the street with “Heil Hitler” and the Nazi salute. About 75% of the Templers were associated with the Nazi party.

In August 1939, a group left to join the Wehrmacht and the British sealed off Templer settlements as internment camps. Before the war ended, most of them had been deported to Australia or sent to Germany, some in exchange for Jews held in Ghettos or camps.

Unexpected evidence of their political activities came to light in a surprising way in 1978 when the owner of a house in Emek Refaim, ironically a Holocaust survivor, discovered a cache of Nazi artefacts in his attic whilst installing a t.v. antenna. I cannot imagine the horror he must have felt. The items included a green-felt Nazi hat, a triangular officer’s patch, an insignia with a swastika and a steel knife inscribed with “Blood and Honour”. They belonged to one Erich Imberger, who lived nearby and hid the items in 1939 when the British began searching for Nazis. and here they remained, for forty years.

Templer schoolhouse, now luxury Heritage accommodation and ancient olive tree.

Today the German Colony is an elegant residential area and it is here that the new Orient Hotel has been built. There is a small museum of Templer history in the hotel and each Shabbat guests can take a tour of the area to see other Templer buildings and the cemetery. It is a cause for congratulation that, despite their inauspicious final days in Palestine, the Orient took the initiative to show the positive aspects of Templer contribution during their early years in the Holy Land.

The hotel has taken infinite care to preserve the original architectural features of the charming old buildings, whilst at the same time complementing them with sensitively chosen contemporary art. In addition the new buildings have superb interiors with many attractive features.

For the last 20 years I have worked as an art consultant, selecting art for hotels in Moscow, Mecca, Mauritius, Milan,Versailles, Montreux, Florida, Barbados, the Dorchester group and more. Consequently I have seen many hotel interiors and in the process have become seriously critical when entering a new establishment. I have on more than one occasion been known to ask hotels to remove certain pieces of art from our room, (much to Charles’s embarrassment) but to my delight there was little I would change at the Orient.

Lighting features

Seating areas

the lobby area

the lobby area

the outdoor terrace and water feature

Whilst walking through the hotel there are features to delight the eye at every turn. I was particularly taken with the innovative and attractive lighting they have installed. As for seating areas to relax, these are plentiful – each one a design delight including those in the open air central courtyard. One of the most impressive features is the central swirling staircase – an architectural joy reaching down five floors.

For over 20 years we have regularly visited Isrotel’s Carmel Forest Spa in the north, so it was good news to discover that we can now walk just five minutes from our home to the Orient, indulge in their spa treatments and enjoy the indoor pool. Add to this the view from the infinity pool on the top floor has to be seen to be believed – overlooking, as it does, the Old City walls. It truly transforms the activity of swimming into another dimension. (spa pool below)

Infinity Pool overlooking the Old City (below)

I have to say that I was not an invited guest at the hotel but merely a visitor for the purpose of completing this story. I did however feel that I had died and gone to designer heaven and, yes, I told the manager I would be happy to sell up and move in. Not only because of the aesthetics, but more important was that the minute I walked through the front entrance I was made to feel truly welcome, an ethos that prevails throughout the hotel. This is no doubt in large part due to the vision of Isrotel’s founder, a wonderful courteous man from the UK, David Lewis. he set the bar for excellence and, were he alive today, he would be justly proud of the heritage that he has left behind.

I have to say that I was not an invited guest at the hotel but merely a visitor for the purpose of completing this story. I did however feel that I had died and gone to designer heaven and, yes, I told the manager I would be happy to sell up and move in. Not only because of the aesthetics, but more important was that the minute I walked through the front entrance I was made to feel truly welcome, an ethos that prevails throughout the hotel. This is no doubt in large part due to the vision of Isrotel’s founder, a wonderful courteous man from the UK, David Lewis. he set the bar for excellence and, were he alive today, he would be justly proud of the heritage that he has left behind.

Another beautiful story and Ruth never disappoints with her reseach and warmth.

I would love to stay at the Orient hotel.

LikeLike

Ruth, how wonderful. You make this history come alive to me. Very interesting now I need to go there and see with my own eyes.

LikeLike